A deep dive into why this point-and-click adventure feels like more than just a video game

[Narrated by Dan Vincent]

Spoiler warning for the entirety of Kentucky Route Zero. If you haven’t played yet, or don’t want anything in the game spoiled for you, turn back now.

Kentucky Route Zero is one of those games where I spent a lot of my first playthrough feeling disoriented. I couldn’t fully decipher my feelings until after I talked through the experience with my roommate. The first thing that struck me from our conversation was, due to the game’s somewhat chaotic presentation of plot, character, and theme, we had very different readings of it. I come from a literary background, whereas she opted to study theater instead. When we started talking about how the game presents dialogue, which is very reminiscent of a script, its design prompted a discussion that made us realize we fundamentally disagreed on the definition of what makes a “play” a “play.”

For me, that type of conversation is standard procedure when I play a game I really love — I dive into YouTube looking for interviews with the creators; I scour the internet for blog posts and Reddit forums to see what other players got out of it; I play the soundtrack on a loop, just to remember the emotional beats that were so well crafted they brought me to tears.

While this research usually helps me gain a more complete, holistic understanding of a game I enjoy, any further exploration into the world of Kentucky Route Zero only complicated things. The more I tried to find others whose experiences playing the game were similar to my own, the more I seemed to come across players who had different readings entirely, like the Eggplant Podcast’s conversations about the game’s nods to architecture and the caving movement of the ’70s and ’80s.

In my initial confusion, I was searching for the one thing Kentucky Route Zero was trying to tell me. The reason I was having so much trouble though, was because the game is not using one character with one story to make one point, but instead presents us with dozens of characters with dozens of stories and no one correct way to think about any of them.

So sure, the game is great and all, but why am I talking about it now, over a year after the release of the final act? Because its chaotic presentation doesn’t just muddy the waters — instead, it’s its greatest strength. That’s what really makes Kentucky Route Zero a timeless and ever-shifting reflection of the society it’s creating a portrait of.

In my eyes, a work is classic if it’s a cohesive, compelling piece of art on its own, but also reveals to us a compelling truth about what it means to be human. After finishing a classic story, we see the world from a perspective we couldn’t have considered without it. Kentucky Route Zero achieves this feat expertly and in more ways than one.

Of all of the dozens, if not hundreds, of references in Kentucky Route Zero, the one that sticks out the most to me as an excellent example of art making us reexamine the world around us is The Grapes of Wrath. Initially published in 1939, the subject matter of John Steinbeck’s novel bears a striking resemblance to Kentucky Route Zero, as it focuses on the plights of migrant workers exploited by the corporations who think of them only as disposable means to an end.

The book’s content is pretty intense and made a lot of readers uncomfortable when it first came out. For instance, there’s a gruesome depiction of characters who can only afford to eat discarded peaches due to their infinitesimal wages, which causes their teeth and insides to rot away.

More than its harrowing examples of worker mistreatment, however, The Grapes of Wrath draws on larger themes of the American dream and the well-intentioned yet ill-fated journeys we take to achieve it. The novel’s Joad family is on a pilgrimage from their home state of Oklahoma to California, where they will presumably find work and make better lives for themselves. As they go about their trip, though, the family becomes better acquainted with the harsh realities of the real world with every passing chapter.

Kentucky Route Zero‘s narrative flips this journey with Conway’s task of completing his final delivery for a dying antique store before he can retire, but the ultimate goal is the same: he is going on a pilgrimage with the assumption that he will be comfortable and happy on the other side. Similar to the Joad family’s increasing desperation to not only find happiness, but survive, Conway’s focus shifts from completing his delivery to his acknowledgment of his own regrets, and his struggle to live with them.

Over the course of the night of the delivery, he becomes less and less concerned with his task and eventually just gets drunk. In a last-ditch attempt to find some sense of belonging on the brink of his impending purposelessness, he willingly and almost excitedly goes to work at the distillery.

The saddest truth of this moment is that he somehow seems convinced that the overbearing Consolidated Power Co. has his best interest at heart — a delusion even the Joads never truly bought in regard to their own subservience to corrupt corporations. In light of their challenging situations, the Joads turned inward to their family for comfort and community. Conway didn’t have anyone left and turned to the only tangible structure around him rather than searching for a new family.

The aching feeling that somewhere else out there, there is a place where we could be better off than where we are now somehow — that’s the American dream, and it’s a feeling we can’t shake in this game. The journey the characters in both of these stories go through is learning that that dream will let you down, and all you can do is make the best of the situation you’re in.

The Grapes of Wrath is unsettling, but for good reason. When the public read the stories of these families’ struggles, even though they were fictional, it was the first time they were forced to confront the atrocities their fellow citizens had to face on a daily basis. Instead of looking away because it was difficult, readers became outraged, and that fervor is what brought about real-world change.

Eleanor Roosevelt, wife of beloved President Franklin D. Roosevelt, was so moved after reading The Grapes of Wrath she traveled to California herself, just to see if workers’ conditions were as terrible as Steinbeck made them out to be. Spoiler alert: they were. Multiple Congressional hearings where Secretary of Labor Frances Perkins advocated for better wages in the 1940s were in direct answer to the outrage the book sparked. The Grapes of Wrath had an impact not only on our nation’s literary history, but its history period.

Although the developers at Cardboard Computer have not specifically cited the book as an inspiration (at least as far as I can find), I can’t help but draw comparisons further than just the subject matter because, to me, Kentucky Route Zero feels like more than a video game. It feels like an essential piece of fiction, regardless of medium, because it so expertly peels back the layers of modern life to show us the broken but beating heart of American society in the same way that a classic novel does. I think that’s pretty cool.

And that’s not to say that allowing ourselves to buy into the uncomfortable emotions this type of art can evoke is no longer relevant. On the contrary, these exact same systems of oppression still exist today, they’ve just evolved into something new. Just look at the way modern mega corporations treat their employees. Amazon warehouses are so unsafe that workers are getting injured on the job in droves, and rideshare companies spent millions of dollars on purposefully confusing marketing to pass Proposition 22 so they didn’t have to give their drivers better pay, benefits, and other protections extended to full employees.

It’s hard to argue that Kentucky Route Zero has a true antagonist, but the Consolidated Power Co. comes pretty close. We feel its influence almost everywhere we go, infecting the land like some kind of disease. They own all of the power, the booze, even characters who are forced to work off their debts. And they don’t let us forget it.

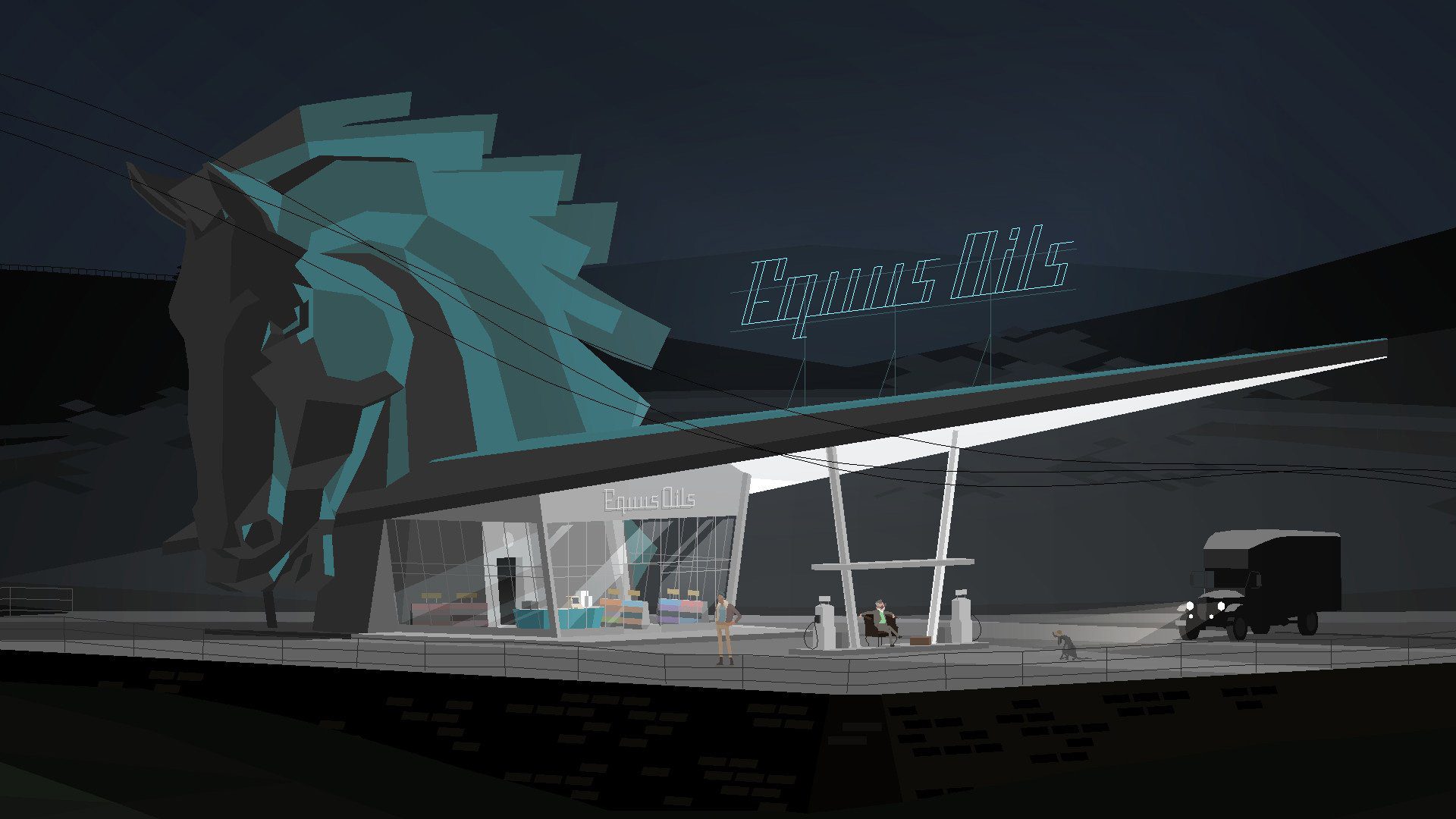

[Image credit: Sam Dibella]

[Image credit: Sam Dibella]

We see it in the larger narrative beats, like the ghostly, flooded mine in Act I or the town in Act V where people were killed because of the corporation’s oversight. It’s also in its more subtle moments, like Dr. Truman’s description of the overly complicated, predatory payment system for Conway’s medical treatment or the solitary phone operator who reminisces about the days before all of her friends were laid off. There’s no escaping it, and we can feel the effects it has had on the region’s people, commerce, and land like an ache in its bones.

The burial ceremony in Act V is arguably the clearest example of this pervasive grief in the entire game. Before leaving their flooded, rundown town behind for good after a storm that all but wiped it out, its former residents bury some of its horses that died in a storm the night before. The town is full of bright sunshine, colorful flowers, and rolling hills. It stands in stark contrast to the imagery of the rest of the game, which is usually shrouded in darkness, both literally and figuratively.

As the group breaks into a hymn during the burial ceremony, dark, haunting ghosts of the town’s residents that died fade into view. At first, there are only a few, but as the music swells, the camera pans out to reveal dozens of these figures, whose numbers overpower the living a few times over.

It’s a chilling moment that moved me to tears (I could write a whole piece on how effectively this game uses music, but I digress), a symbol of remembrance not only for the current residents’ old friends before they moved on, but for all of those who have been lost at the hand of corrupt corporations like Consolidated Power Co.

[Image credit: Kriemfield]

[Image credit: Kriemfield]

This image is already so rich and meaningful within the context of the game itself, as well as the rest of American history, but given the current state of our country, it took on an entirely new meaning. It was impossible to look at those dozens of figures on my screen and not immediately think about the more than 600,000 lives we’ve lost to COVID-19 and the scar the mishandling of the pandemic will leave on our country’s history for years to come.

In all honesty, I could replace any number of works with The Grapes of Wrath, and the comparisons would still ring true. F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman, Lorraine Hansberry’s A Raisin in the Sun, Willa Cather’s My Antonia, Sandra Cisneros’s The House on Mango Street — only a small sampling of literature about the failings of the American dream. However, regardless of which one we pick, the main point of them all remains the same — our disillusionment with our nation’s failure to deliver on its promises is pervasive through all times and to all people, and that’s what makes for a quintessentially American narrative experience.

This perpetual relevance, always lending itself to new interpretations of the game’s content, is what elevates Kentucky Route Zero from a great game to a timeless classic. In its hyper-referentiality, the game’s version of America is eternal. The references of the visuals, language, and subject matter all blend together so seamlessly that we feel we’re not only in a specific time, but in all eras at once. Further, the pervasive grief and sorrow that we can’t quite seem to shake while playing are not just for the few dozen lives lost in a flood, but for anyone who dared dream for something greater.

The game’s characters feel like they could exist at any moment in time, whether it be a hundred years ago or last week, but their plight always feels real, tangible, and affecting. It reminds us that the tapestry of Americana is constantly expanding while simultaneously remaining the same.

One of the pitfalls it could have easily fallen into was leaning too far into that disorder and relying too heavily on its references. Drawing upon classic works and staples of American culture certainly gives a piece the appearance of depth. However, Kentucky Route Zero delivers by not just evoking well-known works of art, literature, architecture, and so on, but by telling us something new about them. By holding a mirror up to the patterns we as a society keep cycling through, it forces us to reflect on why these oppressive powers-that-be keep cropping up and how humanity continues to trudge along in spite of them.

In the same way The Grapes of Wrath‘s significance is carried in its specificity, in its snapshot portrayal of a single moment in American history, Kentucky Route Zero‘s significance is that it is all-encompassing. It zeroes in on the through-line of the American story, on its unscrupulous systems and the effects it has on the vulnerable people within them.

This is precisely why scenes like the burial ceremony feel almost too real — it’s not that the developers at Cardboard Computer can see into the future, but the reality is they were just able to recognize and accurately portray the familiar patterns of oppression in our country and the events that are caused by them.

Kentucky Route Zero‘s true genius lies in the fact that, at a glance, the game looks like complete chaos. The world is not consistent, the characters aren’t fully developed in a traditional sense, and the structure of each individual act is entirely different from the last. Scenes do not build upon preceding scenes — its complexity is harder to trace than that.

However, when we look a little closer, we can see that its story functions differently than we may be used to. Each different scene, character, folk story, line of dialogue, or seemingly random detail functions like an individual stroke of a paintbrush. It’s only when we consider every piece together that we see the bigger picture, the portrait of Americana and the people that make it.

Kentucky Route Zero has cemented itself as one of the greatest games of the decade, but I think it’s even more than that. It’s one of those pieces of art that only comes around once in a lifetime, and I’ll spend the rest of mine trying to untangle every last thread of it.