‘It’s about your birth.’

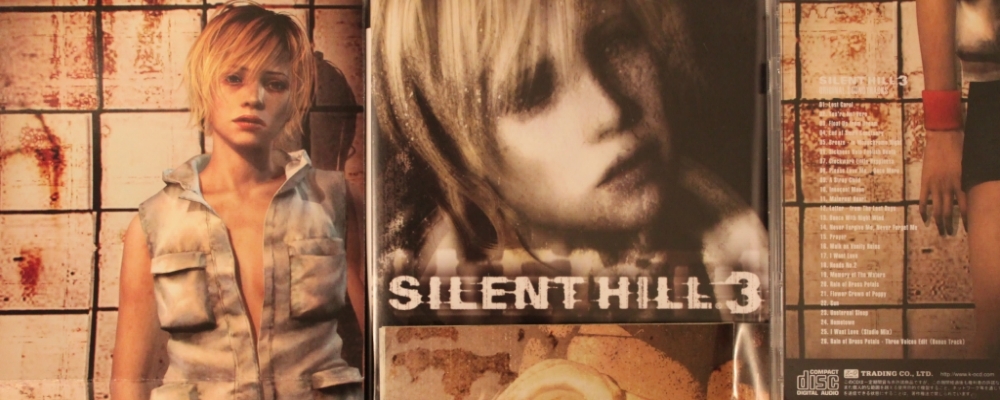

Silent Hill 3 is a mean-spirited game, but then that was always the point. In order to value her future, Heather Mason is dragged, kicking and screaming, through the muck and mire of her past. Yes, she’s given the tools to fight back, but the overwhelming numbers in her way serve as reminder that it’s easier to flee from destiny. Overall, it’s an exhaustive experience; the only relief coming from a goofy swerve, seconds before the end.

Despite what we know now, coupled with the foreshadowing of The Room, Silent Hill 3 always felt like a natural conclusion. Rather than a reflection of its audience, the definitive storytelling is more indicative of a development team coming to the end of the road. The hints are all there – the deconstructive dialogue, the mandated-from-the-top gameplay, and the tongue-in-cheek Easter eggs – and none of it is ever hard to find or decipher.

But the most striking truths are found in its violence. Whereas its predecessors were content with subterfuge, Silent Hill 3’s themes were delivered like the killing blow of a rusty steel pipe.

At its heart, Silent Hill 3 is about a girl coming of age. From the opening nightmare sequence, we’re treated to very familiar horror iconography: blood red hues, a fascination with blades, of something foreign inside the body, and a cute mascot in disturbingly lifeless poses, all set in an abandoned amusement park. Heather’s journey home takes her through teenage hangouts and public places, their dark sides brought to the fore, all the way to Silent Hill and deep within. Little Red Riding Hood by way of Dario Argento, if you will.

Her survival depends on a reconciliation between childhood and adult life, with her former selves being these literal, separate slices of life. By the end, Heather is not Alessa, nor Cheryl, but its through their remembrance that she ultimately becomes her own person, able to make her own decisions in life. On the other side of the coin, there’s Claudia Wolf, the story’s misguided antagonist; a colourless imitation of a reasonable young adult, preferring the comfort of blind faith over autonomy.

Adulthood, or at least what we find of it in Silent Hill 3, is represented by the messes of men. Douglas Cartland is a walking list of mistakes, whereas Vincent Smith takes a perverse pride in belittling the ignorant few. One seeks redemption, the other deals in exploitation. The cast might be minimal, but it works for the duality on display. Lines are drawn and lesson are learned. Douglas, himself, finds redemption through parental guidance, something he thought he’d lost, a lifetime ago.

As a direct sequel to a fairly obtuse original, past events are recalled and plainly deconstructed. Riddle speak is deftly cut down by barbed tongues, infallible fathers are shown to be weak and vulnerable (breaking down our own hero worship in the process), and The Order is explained in definitive detail. It’s this clarity that ends up being vital to Heather’s character growth. Particularly telling is how her descriptive texts turn from dismissive to thoughtful, reflective and empathetic, along with the bloodstains that are eventually splashed across her pure white jacket.

The Otherworld returns to its original form, now a higher-definition of improbable locations, foetal-like defects and rattling heads (for his final game, Masahiro Ito’s designs were part-freakshow, part-macabre fairytale). It’s a harsher world, full of abattoir tiles and maddening works of art, an intensity that almost goes overboard in places; bringing back the surface level scares that were missing in Silent Hill 2.

It’s visceral, but it needed to be that way. The Otherworld doesn’t adapt, it grows with its protagonist. And it’s most obvious in the way the skeletal walls and beasts of raw flesh develop rippling layers of skin as you progress. The Otherworld is a fearful representation of pregnancy and birth, all of which ends with an abortion of sorts.

For a series that prides itself on subversion, Silent Hill 3 is rather transparent with its humanist values. Both pro-choice and nihilistic towards religion, the messages come through clearly at the most shocking of times and even breaks the philosophical fourth-wall when needed (note how Vincent usually addresses the audience through POV angles). At one point, the player is asked to forgive or condemn Claudia’s actions, and the answer doesn’t lie in the usual act of altruism.

Silent Hill 3 will always be most famous for the line, “They look like monsters to you?” but that’s always been a sly misdirection at best, or a love letter by a dev team on their way out. Personally speaking, it’s a symptom of why Silent Hill 3 never crawled out from Silent Hill 2‘s shadow; the constant post-modern distractions took focus away from the bigger picture. But you could also argue that it was down to a waning interest in survival horror, or an emphasis on unrefined combat, badly paced locations, or even the re-use of assets for a quick turnaround. And none of these would be wrong, either.

That said, especially after replaying it for this retrospective, Silent Hill 3 is a game in need of re-appraisal. The tired, introspective tone from the developers is actually more relevant now than on release. Heather Mason also manages to be a strong female character, one that earns that title, rather than put on a pedestal from the get-go. And this was in 2003, remember. The Otherworld was as close as we were ever going to get an HD remake, complete with so many hidden details and huge advancement in character design. And it’s rarely said enough, the haunted house section is completely underrated in the way it pulls the rug from underneath the player.

Hey, maybe, ironically, it’s a reconciliation with the past speaking. In any case, no matter where you place it – best, mid-tier, worst (personally, mid-tier) – Silent Hill 3 signaled the dying days of “Team Silent,” but there was one more oddity that would send us tumbling down the rabbit hole and into a realm of existentialism that hasn’t been explored in video games since.