Baka mitai

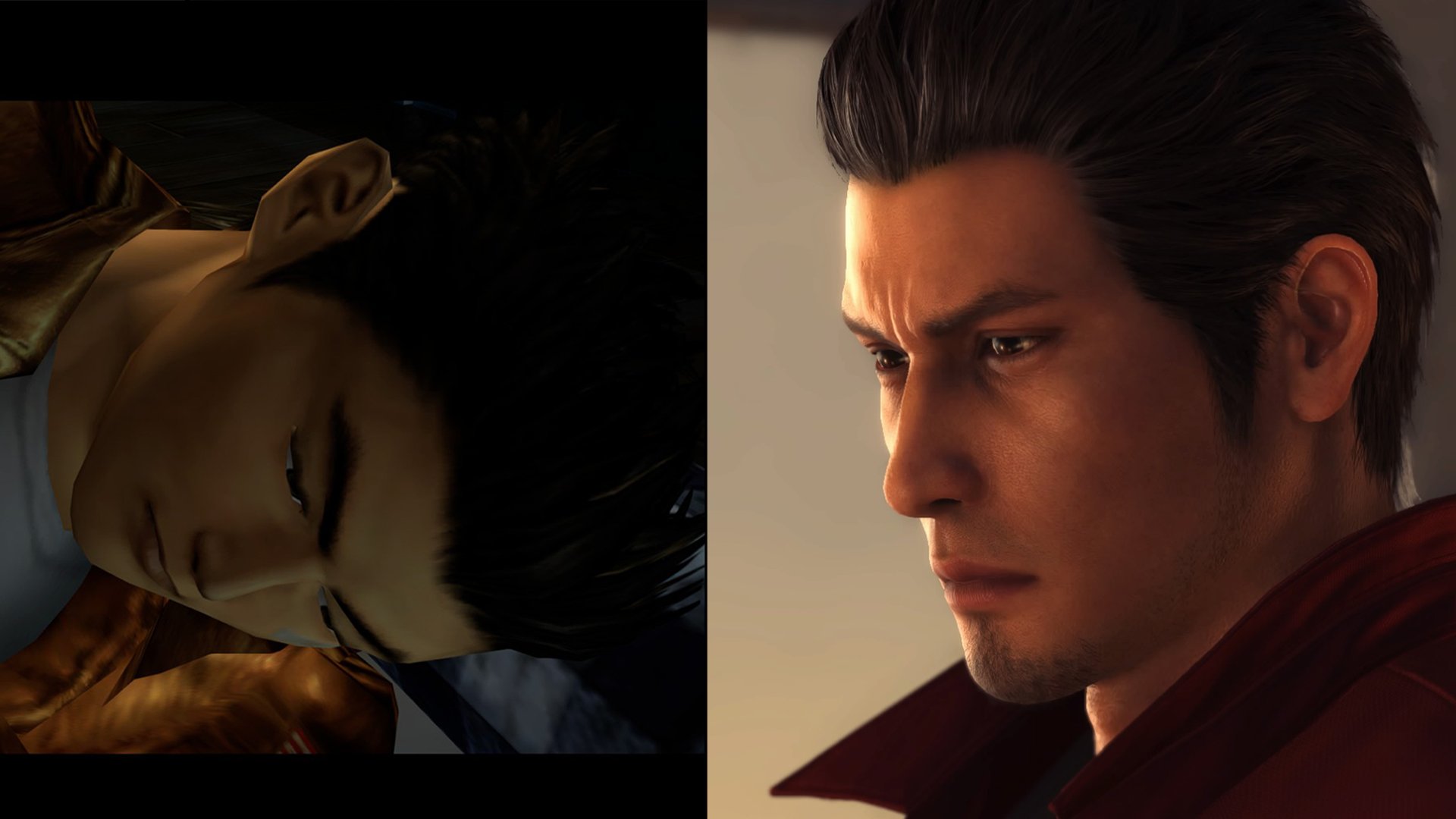

For nearly as long as I’ve been playing Yakuza games, I’ve always read comments from fans saying, “These games are like Shenmue”. At first glance, that definitely sounds accurate. I even remember making such a claim after playing the demo for Yakuza 3, which reminded me a lot of what I had heard about Sega’s Dreamcast classic. It has taken me until now to see how wrong that statement is.

For those unaware, I’ve never personally owned a Dreamcast. My friend had one and I’ve played games on it, but the consumer distrust that Sega bred after the release of the Saturn got to me even in my youth. I absolutely loathed Sega’s 32-bit system and I didn’t want anything else to do with their consoles for the foreseeable future. Maybe it was just my nine-year-old self being hyperbolic, but I wrote off the Dreamcast long before it was even announced as coming west.

While that may or may not be a tragedy, it was how I felt at the time. That decision ended up causing me to miss out on some crazy and memorable games from Sega’s final console, most notably Shenmue. I’ve never had a frame of reference for properly comparing Yu Suzuki’s magnum opus to Yakuza, but after reviewing the two games this past week, I can finally make a declarative statement.

Shenmue and Yakuza are really not that similar.

To an outsider, a cursory look might trick you into thinking both series are the same thing. Shenmue has you traveling around Japan and China in a semi open-world manner. You can talk to people, play mini-games, enter shops to buy items and even fight guys on the street. Yakuza is limited to Japan (with different cities), but everything else I mentioned above is accurate of Kiryu Kazuma’s journeys. The execution of these ideas is where the two series differ.

The main goal with Shenmue was to create an environment and atmosphere that could be mistaken as real. The famous concept behind Yu Suzuki’s epic is an acronym known as “FREE”. This stands for “Full Reactive Eyes Entertainment,” and it was a core philosophy that Suzuki and his team worked to embed in everything Shenmue had. If you wanted to talk to a random person, that should be possible at all times (and even fully voiced). If you wanted to chill out and play some arcade games, that should be possible whenever you felt the urge.

There was a story with main characters in Shenmue, but the real desire was to expand the possibilities of gaming by presenting entirely new dynamics not feasible on older hardware. This can be seen in how progressing through the main campaign of the first Shenmue puts more of an emphasis on mundane activities over bare-knuckle brawling with thugs. For a martial arts game, Shenmue features very little fighting and a weird focus on living out Ryo’s real life. It even culminates in him getting a job to pay for a ticket to China, which is the kind of stuff kung-fu films gloss over.

Shenmue even presents different scenarios based on when you appear to specific locations or on what in-game day you’re finishing a main story sequence. There is a tremendous amount of missable cutscenes and content because real life has much the same thing. If you aren’t at a bar on Christmas Day, you might miss the chance to profess your undying love to your high school sweetheart.

For the Yakuza series, the main goal was to create a gaming experience geared more towards adults. At the time when Yakuza released in Japan, Sega was famously dealing with financial woes. The failure of the Dreamcast was still fresh (with Shenmue playing a huge role in that) and market trends were showing Sony and Nintendo making pushes towards teenagers. Microsoft had also jumped into the console market and it seemed like the medium was starting to “grow up”.

Instead of trying to create a game with mass appeal, Yakuza series producer Toshihiro Nagoshi wanted to make a game specifically for the Japanese market. Sega wasn’t doing well in any regard and Nagoshi figured honing in on something only they could provide would resonate with a home audience. After some extensive research (a.k.a. drinking at dive bars in Tokyo) and hiring a famed Japanese crime novelist, Nagoshi’s team set out to properly replicate the Japanese underworld and show that gaming could move past being simply high scores or quarter munching.

With that, the very opening of the first Yakuza should show you how different both teams approached game design. Yakuza sets up a clear story, has intense cinematic direction and incredible voice acting and always guides the player through the journey to maintain proper pacing of its plotline. There are side distractions, sure, but you likely will never be without an idea of how to progress in Kiryu’s story.

The emphasis that Shenmue puts on fleshing out its setting of Yokosuka, Japan is not present in Yakuza’s fictionalized version of Tokyo. There is a layer of authenticity to how Ryu Ga Gotoku Studios’ created Kamurocho (Yakuza’s main setting), modeling it closely after Tokyo’s own Kabukicho district, but you never have the same level of interaction as present in Shenmue. Nagoshi’s team certainly wanted to create an environment you felt connected to, but wisely stepped away from detailing too much of it and focused more on fleshing out other aspects of the game.

Even the side activities in Yakuza don’t take center stage. You could make that same argument for Shenmue, but Yu Suzuki’s vision includes waiting around for multiple in-game hours while time passes and new events can occur. This necessitates doing something to kill time, which is where the arcade cabinets (or gacha dispensers) come in. In Yakuza, the only thing stopping you from progressing is walking to the next waypoint.

Beyond that, even the pedestrians present in Yakuza bear little resemblance to Shenmue’s obscene level of detail. Since there isn’t much story purpose in talking with random bums or little children in Yakuza, the game doesn’t allow you to do so. Some NPCs might give a single line of dialogue, but that is it and you’re on your way. In Shenmue, you’ll be talking to seemingly everyone since the game demands you piece clues together on your own.

The action sequences, as well, play out with entirely different design methodologies. Shenmue uses an engine repurposed from Virtua Fighter (of which the game originated as a prequel to the fighting series) whereas Yakuza could be more closely linked to Streets of Rage. Shenmue wants you to practice your martial arts, focus on skills that you find useful and execute them like a true master of kung fu. Yakuza just lets you smack dudes in a visceral manner with simplified inputs and combo strings. You even get RPG-lite systems that see Kiryu level-up, where Shenmue is mostly about your own journey with conquering its control scheme (though moves will get stronger as you use them).

What you prefer is entirely subjective, but each game feels nothing alike. I guess removing layers and layers of nuance will reveal the central idea of “Martial-arts action,” but the execution is key. Both games couldn’t feel less alike if Sega tried. Even the quick-time events play out differently, with Shenmue relegating entire sequences to them while Yakuza uses them to punctuate devastating finishers in combat.

Could one even say any aspect of the two series’ is similar? For sure: there is definitely some crossover between the two series. In action, though, you really don’t get the same thing playing one over the other. Both are targeted at a different audience and mindset and that is completely okay.

What drew me to falling in love with Yakuza was split between the writing of its characters and its mixture of old-school, arcade gameplay design with new technology. What I enjoyed from my time with Shenmue was how it made you feel organically connected to its game world and the respect it paid to martial arts philosophy. Any influence that is present is likely because Nagoshi worked as a supervisor to Suzuki while Shenmue was being made.

Really, though, just stop comparing the two series. Each does something totally different and it is really diminutive to try and say they are the same. If Yakuza is Shenmue, then Deadly Premonition is Shenmue. Resident Evil 4 is Shenmue. Heavy Rain is Shenmue. The impact of Sega’s legendary game can be felt in so many titles that you can see it in even the most far removed of genres. That doesn’t suddenly mean that these games are similar to Yu Suzuki’s.