I had my Christmas on Stardoll

The first way I spent the holidays online was through dress up games. Of course, this is second to gawking at my cousin’s MySpace as an eight-year-old on Christmas, wondering why the fuck Tom was in her top eight friends list. But in that same single-digit section of the 2000s, nothing made me understand myself as a girl online quite like dress up games did.

If you weren’t still picking your nose in 2008, here’s the dress up games rundown: virtual dress up games have been around nearly as long as the internet has, with the first games cutesifying screens in the late ’90s. A 2014 essay in Kill Screen (required reading if you want to know more about dress up games’ history, by the way) notes that the first dress up games were more interested in the “sexual allure of an illustrated girl,” and were mostly played by manga fans.

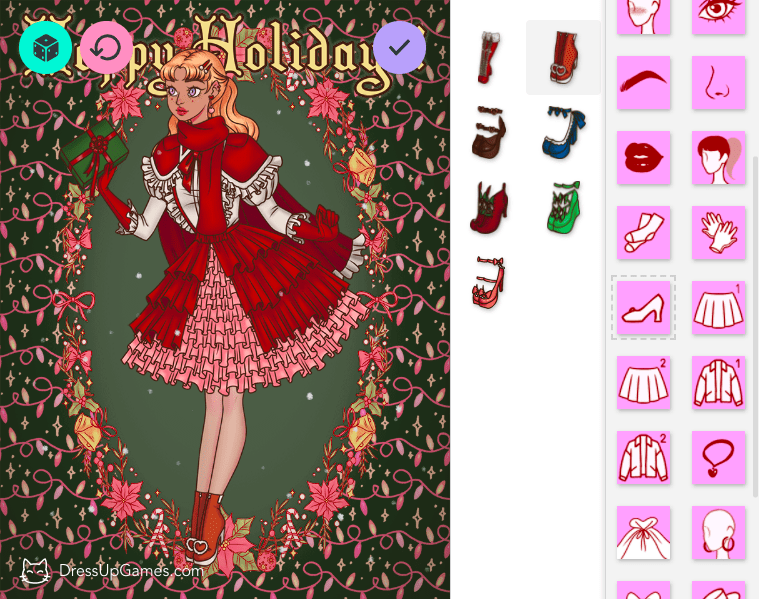

But that didn’t last for very long. Dress up games for girls flooded a Flash-player-ready internet, and brands like Mattel decided to capitalize on it by moving their plastic dolls online as early as 1996. My personal favorite sites were DressUpGames.com, which is as old as me, founded in 1998 and still kicking, and Stardoll.com, which was created by paper doll enthusiast Liisa Wrang in 2004.

Dress up games as a lone, glittering bastion in a field of blue-and-grey shoot-em-ups lead to a lot of games going overboard with the whole “for girls” thing. As that Kill Screen essay notes, “Stand alone dress-up games operate under the assumption that their audience has a one-track mind. Because do girls even like anything other than princesses, fluffy puppies, baked goods and pink everything?”

But I always looked forward to holiday dress up games, which were like red and green jewels to me. They encouraged me to get lost in fantasy, something I needed since my real-life holidays were often smudged by tears and a very unhealthy family dynamic. As a child, I felt safer with the gorgeous, forever-smiling women in my games, who showed me who I might aspire to be as a woman. I didn’t want to be a screaming, crying grown-up; I wanted to wear the cranberry ball gown with the white fur trim. When the game allowed me to, I made my virtual doll’s skin a little bit darker, her irises and hair nearly black, like mine.

No little kid wins when their games show womanhood as being only one thing. I’d love to see more diversity in all games, and I know I could have used it when I was a little girl, looking to my computer to show me the woman I might one day become. But there’s still something romantic about the stereotypical beauty of dress up games. They let you escape into a type of womanhood that’s easy, more palatable, with a constantly regenerating, full closet. Like with the rest of the holiday season, I’m sure that my finding any nostalgia in that is just a lifetime of successful marketing at work. But sometimes it’s nice to pretend.