This DOES impress me much

[What’s the best way to make Destructoid’s Front Page? MS Paint illustrations and Shania Twain references. Obviously. Oh, and you also have to write a super kick-ass blog that delineates the difference between a gaming companion being merely a gameplay mechanic and actually being an extension of the player via emotional connections and willing utility. Obviously. genoforprez kicks off his campaign for the office of Destructoid’s heart with this super in-depth, interesting, and encompassing read pointing out what makes Yorda a great gaming companion and Elika a glorified button prompt. – Wes]

Hello Destructoid community! I am a long-time visitor and commenter but baby blogger. This will be my first blog on the site, but I hope to continue sharing my thoughts on other topics in the future. Nice to meet you!

Recently, while revisiting two of my old favorites, I noticed a very superficial similarity between ICO (PS2) and Prince of Persia (Xbox 360) – i.e. the fact that both games put the player in the role of a male adventurer with a loyal and dependable female companion in tow. ICO, despite an appearance that has not aged especially well, remains an undying classic in the hearts of many players. Prince of Persia is fondly remembered for its breathtakingly beautiful art, but despite being a good game in its own right, it’s not quite a classic on the same level as ICO, and the player/AI relationship does not seem to be a similar source of fondness.

I have heard players wax poetic over the sense of sharing a warm, empathetic relationship with silent, pale Yorda. Why did Yorda garner this sort of response from players? Why do they still remember it fondly all these years later? While we admittedly don’t know that Elika’s creators intended for her to have the same effect, we might still ask: Why does Yorda garner these feelings of warmth and empathy whereas Elika does not (or does not appear to do so as strongly)? What makes the difference?

I spent an evening switching back and forth between the two games, playing a little bit of PoP, then a little bit of ICO, then repeating, and trying to think about what made these two relationships feel different – not just narratively, but mechanically. I wanted to analyze it in video game terms.

In the end, I came up with five essential areas of difference between the Prince/Elika and Ico/Yorda relationships, and I took the extremely unnecessary but potentially helpful step of creating some highly professional visual aids to help with the explanation. I, um…I made them in MS Paint. They’re actually quite bad. Ahem.

So let’s get down to business! How does Yorda manage to garner so much player empathy, but Elika doesn’t seem to garner very much in comparison? Specifically, what do the games do with mechanics and AI that results in this difference? Here’s some thoughts.

Key for visual aid (very sophisticated!)

Observation 1: The player’s freedom to “CHOOSE” empathy

The highly professional and no doubt artistically pleasing visual aid above hopefully illustrates the difference between a situation where the player “chooses,” or must actively perform empathy, versus a situation where the empathy between the characters feels more prescribed. It’s like showing versus telling in gameplay terms.

In PoP, as the player is jumping over gaps, running along walls, swinging from hooks, and all manner of other acrobatic type stunts, Elika just floats along behind the player like a balloon at the Macy’s Day Parade. The player is never required nor given the option to assist her in any way. She clings to you like a koala bear, whether you invited her to or not.

Compare to ICO, where Yorda sometimes follows you but often doesn’t. In fact, she often just goes wandering off with her head in the clouds. This means sometimes the player must call her over to do something cooperative, which invokes a sense that Yorda is her own person acting on her own whims. She is not set to auto-follow your every action but must often be requested to join you (e.g. by holding out your hand to her and waiting patiently for her to accept it). When she accepts the player’s request, I believe something very small and subtle but emotionally important happens. ICO is designed in such a way that the actual, human player is able (and willing) to extend a helping hand to Yorda and have her accept the offer. In this way, the player is performing empathy in the first-person. PoP is designed in such a way that the player merely watches empathetic behavior taking place between two characters in a third-person sort of way. For players who view their avatars as in-game representations of themselves, that more prescribed presentation of empathy may feel contrived and unsatisfying.

Observation 2: A feeling of mutual independence

The best thing about Elika is that she never leaves your side. The worst thing about Elika is that she seriously never, ever leaves your side. She’s clingy, to put it bluntly. Literally and figuratively.

Yorda, though? I mean, she’ll cling to your hand if you ask her to, but as soon as you let go, she wanders off to investigate some interesting-looking rocks or whatever captures her attention. She is her own person. Call her when you need something, okay? For the player and Yorda, it’s okay to split ways and do your own thing, then get back together a few moments later. And when you’re off doing your own thing, Yorda is off doing her own thing. Just two independent people exploring whatever tickles their personal curiosity. For you, it’s levers, switches, things to push or climb on. For Yorda it’s birds, shiny rocks, other more different rocks. Don’t judge her interests, okay? She’s her own person. You get the idea.

Elika, though? She wants to be where you are, doing what you’re doing. She wants to be involved with every moment and aspect of your life, and she does not exactly leave this up for discussion. However nice and helpful she may be, she is a little bit of a human collar around your neck.

Observation 3: Game mechanics are not people

I feel like this one is pretty important, and I have read several game developers’ blog ideas along these lines in the past. The basic idea is that a companion character must feel useful to the player for the player to feel positively about them – which is true! Players want a competent and contributing partner on any team, whether that partner is human or AI.

But.

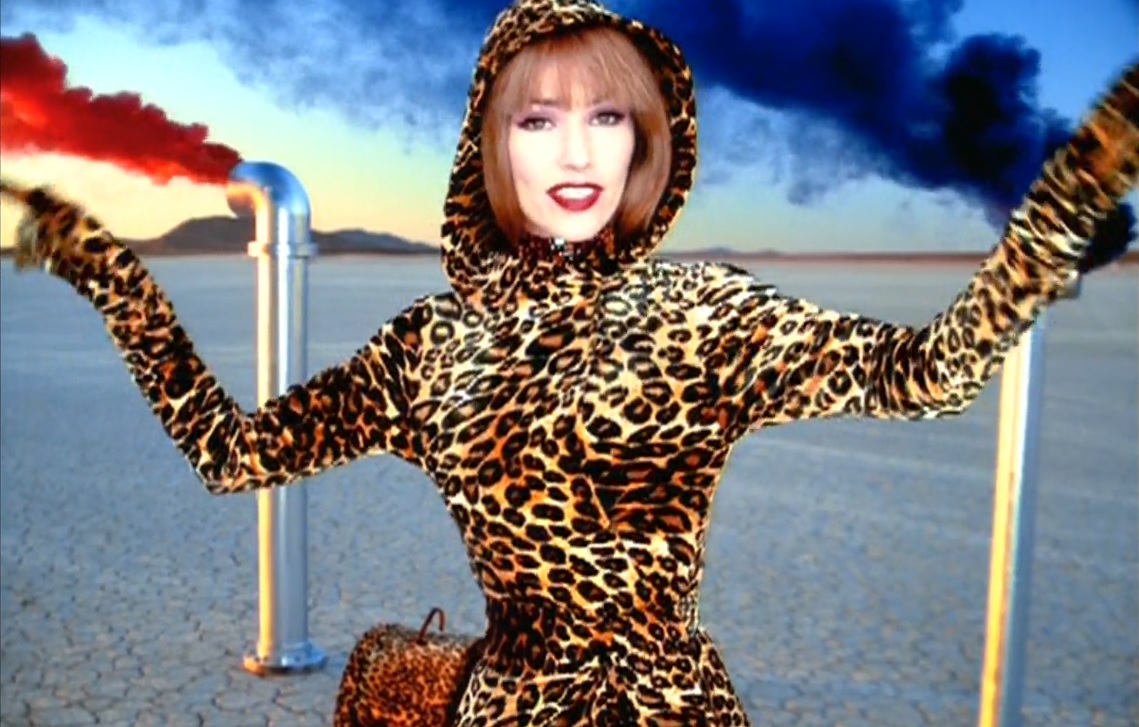

While competence guarantees that the AI companion will not annoy the player to the point of rage, it is not sufficient to make the player feel anything special or extra toward that AI companion. Pardon my outdated Shania Twain reference, but: “You’ve got the brains, but have you got the touch?“

When you think about the way that Elika is useful to the player, you find that her ways of assisting you are very similar to the kinds of independent actions you are already taking yourself, such as running, jumping, attacking, and so on. Press A to jump. Press Y to have Elika extend your jump. When you really stand back and look at it, a lot of other games would just have you press A again to double jump – no second character required. The more I thought about it, the more I started to see Elika as just a human name given to the player’s own actions. Technically, her contributions are the very definition of “useful,” but they feel a little too much like a function called by a button press. They lack a certain human touch in practice. There is a certain “Press Y to Elika” about it.

Yorda again does some things very differently from Elika here. While she is a bit of a space case, there is interesting design to her madness. While the player is running around a room trying to identify the puzzle and its parameters, Yorda is usually wandering around being intrigued by such fascinating things as dirt, rocks, metal, bigger rocks, etc. But amidst all her spaciness, she is also a subtle HINT system. When the player manipulates something which effects a change in the room, Yorda will sometimes take sudden and extreme interest in a particular area and glide over to examine it. The way she marvels at things is sometimes just her strangeness, but other times she is subtly guiding you toward points of interest.

This is notably different from Elika’s style of assistance in that Yorda’s assistance is not button-mappable; you don’t press Y to receive help. Instead, the actual player has to observe a change in Yorda’s behavior, take an interest in it, and then observe what she is doing in order to discern a possible message. This is going to sound very demeaning to Yorda, but you could almost put it in Lassie terms: “What is it, boy?! You smell something behind the third pillar on the right?!” Yorda subtly offers hints to the player if the player chooses to pay attention to her behavior and its connotations. The player assists Yorda if she “chooses” to take the player’s hand. The game is cleverly designed in a way that feels like Yorda and the player are continually opting into each other’s help.

It feels good to deliberately choose someone even when you don’t have to. It feels good when someone chooses you even when they don’t have to.

Observation 4: Bonding through gratuitous interactions

In a lot of games – not just Prince of Persia – the gratuitous interactions with ally characters too often boil down to pressing a button to initiate a short dialogue quip or a pre-recorded conversation. My sense is that, while this might expand the player’s narrative-knowledge of the relationship, it doesn’t really change the player’s emotional experience of the relationship all that much. If this relationship is a story we are watching like a film, then that’s fine; but if the actual human player is to feel warmth, empathy, or attachment to their AI friend, then maybe the yack track doesn’t get you very far.

ICO, naturally, has the famous hand-holding mechanic, which is sometimes functional, but often completely gratuitous. It is an action taken for its own sake. You hold hands because it feels nice to be holding hands.

Holding hands also changes the physical feel of your movement, so there is a tactile difference to buddying up, whether it’s goal-oriented or just affectionate. That tactile feedback is informative, sure, but maybe it also just kinda feels nice? By comparison, Elika’s clinging has basically zero weight or friction, which makes her companionship feel a tad illusory.

I have an odd but very strong suspicion that the physical feeling of holding Yorda’s hand has something in common with the phenomenon of players developing a real feeling of companionship with their in-game horses (or other mounts). It makes that companionship tangible. A horse may be fast transportation, and it may even join you in combat, but you need look no further than Shadow of the Colossus to know that a horse can also be so much more than that. Does riding a horse not feel like bonding with it over time? Does it not change your movement in a tangible way such that partnership feels different (better) than isolation? You pull the reigns of the horse to tell it where to go, like pulling Yorda’s hand to guide her out of danger. The horse or Yorda could kick you and reject you, but instead they trust you, and you trust them; you feel that in a physical way, for hours and hours of in-game experience, and it has a subtle but very warm effect.

I remember playing Brütal Legend and feeling a sense of bonding during certain team-ups with the AI teammates – but none of those team-ups were gratuitous (they were always combative/strategic), and they were always very short in duration. I remember hoisting a Razor Girl up onto my shoulders and thinking to myself: Imagine a game where the player hoists an AI friend up onto his shoulders and carries that friend around because it just feels nice to do that. Suppose it were a game where a mother or a father figure could hoist an AI child figure up onto their shoulders and carry them around in the game world, maybe for gameplay reasons, but also because affection is its own reward.

Observation 5: Game mechanics are not people redux

How do Elika and Yorda differ in combat situations? About as widely as possible!

Elika suffers the same problem in combat as she suffers in platforming: She feels a bit like a second character model tacked onto the player’s own independent actions. In combat, enemies in the game will sometimes cloak themselves in a black murk that makes them invincible to basic attacks unless the player presses Y to summon Elika out of thin air and have her leap at the enemy’s face, blasting them with light like a human flash grenade. Tellingly, if the player misuses this ability and it fails, Elika is knocked unconscious and does not revive again for a short while, making her abilities inaccessible to the player. In other words, Elika is one of the player’s “spells” and she even has a cooldown.

On memory, I remembered Yorda being utterly useless in combat. She served absolutely no purpose other than as a damsel to be rescued and protected. However, when I got back into the game, I found my memory didn’t quite do her role in the combat justice.

What you find is that the shadow monsters try to avoid you or wait for an opportunity to creep up on you and attack. They also try to divert your attention away from Yorda so that other shadow monsters can sneak in and steal her while you’re distracted. Knowing that abducting Yorda and pulling her through a spawn point is their end goal, though, is also the key to your strategy. When the shadow monsters are circling around you but evade too quickly for you to hit them, you can put some distance between yourself and Yorda to divert their attention and tempt them to close in for the steal. Then you charge them with your wooden plank, swinging like mad.

It seems counter-intuitive at first, but it’s often a good idea to grab Yorda’s hand and lead her directly to a shadow monster spawn point. If they grab her and you’re far away, you may not reach her in time to rescue her. But if you are right next to a spawn point, you know which one they’ll take her to (nearest) and you’ll be right there to pull her out when they try to drag her through.

In other words, whereas Elika is in essence just another one of the player’s attacks, the combat strategy in ICO revolves entirely around Yorda. Yorda is, essentially, the ball in the game of ICO. When Elika goes down in combat, there is nothing you can do for her, but she’s also not in any real danger anyway. The only thing you feel about it is the length of the cooldown. But if Yorda gets taken, your entire strategy changes immediately. The whole point of the combat is to protect your friend and keep her safe, yes, but it’s not just about keeping her HP from dropping to zero (thus avoiding the dreaded escort mission).

Yorda makes the combat part tug-of-war, and part cat-and-mouse. The enemies are trying to pull her away from you into oblivion, and you are trying to hold onto her. That in itself has more emotional impact than just stopping bad guys from beating on her. But since the strategy of the combat can also mean using her as bait from time to time, the combat is also about letting go of a helpless friend’s hand in the height of danger and asking her to trust you, assuring her that you’ll be back before anything bad happens, while not being 100% sure if that’s actually true…

…but you gotta keep up that cool confidence, right?

The fact that the game does so much outside of combat to make you care about Yorda once you stumble into it should not be ignored. It’s very possible the combat would not evoke these feelings if I did not already feel a certain companionship with Yorda going in, which the combat only reinforces.

Final Thoughts

I’ve struggled to come up with a concise way of expressing all of the above in a neatly-packaged TL;DR format. I’m not even sure I’ve done a good job explaining in the examples above. Maybe the core idea is that players may be more likely to feel empathy – whether it’s for a mute girl you found in a cage or a horse you found and tamed in the wild – if it feels like both parties could leave at any time, yet they choose not to. Choosing to stay must have practical benefits. Yes, a competent partner is very useful; but it must also have emotional benefits – holding hands or hugging your horse are tangible things that just feel good.

Companion Cube gives you a practical boost, sure, but you also hold down that button to carry Companion Cube with you, as if holding its hand or tucking it under your arm, from one adventure to the next. The idea for Companion Cube was born when it was observed that players could stop holding the cube when it was no longer useful to hold it…but they chose to keep holding it, and keep on holding it – even though it had no dialogue or animations or further use! They didn’t keep it because it was useful or competent (although it was both of those things). They kept it because it felt bad to leave it. Not just because something useful was being taken away, but because they were essentially being asked to stop holding hands. But they didn’t want to. Holding hands feels good. When given the option, it feels good to keep holding hands.